- Home

- David Rosenfelt

Who Let the Dog Out? Page 2

Who Let the Dog Out? Read online

Page 2

It’s hard for me to accurately take in the scene, because I’m trying to do it while gagging, screaming, and running out of the room. As I’m leaving, Pete and Willie have heard me and are running in. They’re going to understand my reaction soon enough; there’s no reason for me to stop and explain it to them.

I run out on the porch and try to take deep breaths and avoid throwing up. I haven’t thrown up since I was a kid, and just the memory of how awful it was makes me want to throw up. I can hear Pete yelling something inside the house, but I can’t tell what it is.

Moments later, Willie comes out with Cheyenne on the leash, and he hands it to me. “Keep an eye on her,” he says, and when I take the leash he goes back into the house.

So I’m left on the porch, simultaneously retching, gasping, panicking, and holding a leash. Fortunately, I’m a multitasker.

It’s less than five minutes before the police cars start to arrive, and there must be ten of them. Pete comes out to talk to two of the officers. Pete is a captain in robbery/homicide, so I assume he’s in charge, and just consulting.

He hasn’t said anything to me since we discovered the body, but when he sees me still on the porch, he comes over. “You and the dog should wait over there,” he says. “You’re going to need to give a statement.”

“You know everything I know.”

He nods. “We have to get it all on paper.” Then he points to Cheyenne. “Too bad he can’t talk.”

“She.”

“What?”

“She’s a female. Her name is Cheyenne.”

“Thanks,” he says, with a slight frown. “That’s just the kind of information we need.”

“What’s the victim’s name?” I ask.

“According to his driver’s license, Gerald Downey. You know him?”

I don’t, and I tell him so. Then, “Any evidence of a break-in?”

Pete frowns again. “You conducting a formal investigation? Or maybe looking for a client?”

“No chance. My last client was such a pain in the ass, I’m retired.” Since Pete was my last client, the dig isn’t that subtle.

“The back door was open; that could have been the point of entry, and it’s possible the perpetrator took off that way when we showed up. The wound was very fresh.”

“I noticed,” I say. “And after our statements, we can take Cheyenne back to the foundation?”

He nods. “Yeah. I don’t see her as a suspect. Maybe you can represent her in a civil suit.”

Crime scenes take forever to process, and when the crime is murder, then “forever” understates the case. It’s almost three hours before Willie and I give our statements and are cleared to leave.

Willie has Cheyenne’s leash, and he comes over and says, “I’m going to take her home with me, just in case.”

“Okay.”

“You get a look at the guy’s face?” he asks.

“Not really.… Once I saw it wasn’t attached to his neck, I didn’t really focus on it.”

“I did; he came in yesterday. Said he was interested in adopting a dog.”

“Which one? Cheyenne?”

Willie shrugs. “I don’t know; it never got that far. I asked him where the dog would sleep, and he said he had a doghouse, so I got rid of him.”

“He was probably just checking the place out,” I say.

Willie and Cheyenne leave, and before I go I find Pete and ask him if he’s learned any more about the victim.

“Did I say anything to give you the impression that you and I were conducting a joint investigation?” he asks.

“A guy steals my dog and then gets murdered; I can’t help but wonder if the two are somehow connected.”

“Your dog wasn’t the only thing this guy stole.”

“He had a record?”

He nods. “That’s understating it. Been a thief his whole life, spent a bunch of it doing time. Hasn’t been arrested in the last two years, which is a record for him.”

“What did he steal?”

“Let’s put it this way: I think until tonight dogs were the only thing he hadn’t stolen. Probably had it on his bucket list before he kicked it.” He pauses, then says, “Just got it in under the wire.”

There’s nothing left to be learned from Pete tonight, so I go home to Laurie, who is awaiting my arrival so eagerly that she has fallen asleep with anticipation.

I take Tara and Sebastian for their nightly walk. Tara is a golden retriever and the greatest dog in the history of the universe. Sebastian is the basset hound we adopted as a package deal along with Ricky. It is poor Sebastian’s plight to forever be the second best dog in the house, but he seems to accept it and deals with the humiliation pretty well.

I plan a ten-minute walk, but they appear to enjoy it so much that I extend it to a half hour. When I get back, Laurie has awakened and is sitting up in bed waiting for me.

I had called her from the scene, but now I explain the night’s events in more detail. “You think the murder and stealing the dog are connected?” she asks.

I shrug, which is what I do when I don’t know something. I find that I shrug a lot. “Beats me.”

“You going to look into it?”

“Maybe. I’m curious about it.”

Unfortunately, the conversation doesn’t get any more insightful than that, and finally she brightens up and starts telling me about the rest of the baseball game. “Ricky hit a home run!”

“He did?”

“Well, I’m not sure it’s officially a home run. He hit it about five or six feet toward third base, and then the other team kept throwing the ball away, and he ran all the way around the bases. Then he started going to first again; he thought he could just keep running until they tagged him. It was adorable and he was so excited; I wish you had seen it.”

“Aggressive on the bases, and always looking for that extra edge: that’s what I like to hear,” I say. “I worked with him on that.”

“Don’t tell him I told you about it,” Laurie says. “He wants to tell you himself in the morning.”

“Did you talk to the coach about the right field thing?”

She nods. “I did more than talk. I pointed my gun at him and told him either Ricky plays shortstop or the team will be minus one coach.”

“Perfect. What did he say?”

“He refused, so I shot him.”

“That’s my girl.”

If you are antisocial, far northern Maine is the place for you. Of course, other preferences and characteristics besides not liking to have people around would help as well. You should be rugged, like living off the land, not care very much about eating out and cable TV, and have a healthy disdain for paved roads.

That’s not to say there are no people to be found. There are even a few small towns here and there … mostly there. They are nothing much to speak of; in this area three hundred people represents a bustling metropolis.

But the citizens of these towns are for the most part hardworking, self-sufficient, decent people. And those are the kind of people who occupy Fleming, Maine, population 248. Fleming sits about six miles from the Canadian border.

There is another small community, about twelve miles west of Fleming. Populationwise it’s far smaller, numbering thirty-one people, a third of whom are Americans. It’s not on any map, nor does it have any kind of official government. Its people have only lived there for three weeks, and they have essentially blended into the land, living in caves and camouflaged huts. They don’t have to farm the land: they have their own supplies, enough to last them for another three months.

That is much more than they will need; they will very likely all be dead well before that.

The citizens of Fleming have no idea that this community exists. The people almost never come into town, or make their presence known. They have sent in two of their group, under assumed names and false identities, to get something they hadn’t anticipated needing.

Before long, when they get the wo

rd, they will break into units of two and three and travel south. They will take back roads, which is pretty much the only available roads anyway.

They will head to a small town called Ashby, which is actually an island, connected to the mainland by a small bridge. There are 740 people in Ashby at this time of year, far more than in the winter.

The people of Ashby are not expecting these visitors, and their town was chosen for no reason other than unlucky geography. It is situated perfectly: if there were a bull’s-eye, Ashby would be in the center of it. The citizens of Ashby will not even realize the invaders are there until it is too late.

By that point their fate will have been sealed.

Coincidences bug me. They don’t bug me as much as people who wait until all their groceries are rung up before reaching for their wallet or opening their purse. And they don’t bug me nearly as much as drivers I wave ahead of me, who then neglect to thank me. Or as much as football announcers who refer to simple blocking as putting “a hat on a hat,” or who say that the solution to a team’s problem is the need to have someone “step up and make a play.” And coincidences don’t bug me anywhere close to as much as DVD packages that can only be opened with a chain saw.

But they do bug me, and I basically don’t believe in them.

As coincidences go, this would be a pretty big one. Literally minutes after entering our foundation building, going directly to Cheyenne’s run, and stealing Cheyenne, Gerald Downey was brutally murdered.

Very little of it makes sense, at least at the moment. If Cheyenne was Downey’s dog, and she got lost, then why go through the elaborate theft? He could have simply showed up at the foundation and provided evidence of ownership, and we would have turned her over.

That evidence would have been easy to provide, be it vet records or even a photograph. Everyone has some photographs of their dog, even slimeballs like Downey. We have no interest in making it difficult for owners; we want them to reunite with their dogs.

If Downey did not own Cheyenne, then why steal her? She’s a great dog, but there are thousands of great dogs available in area shelters and with rescue groups. She’s a mutt, so she would have no value if he was looking to sell her.

Maybe Downey was stealing her for someone else, and for some reason that other person couldn’t or wouldn’t come down to the foundation and identify her as his dog. Might that person have killed Downey? But if he did, why not take Cheyenne? If she was important enough to hire Downey to steal her, why leave her there?

As I may have mentioned, these are the kind of questions that bug me.

I want to talk to Laurie about it some more, but I can’t do it at breakfast. Since Ricky has joined our family, we try and eat as many meals together as possible. Occasionally our schedules prevent us from all being home for dinner, but when it comes to breakfast, we’re pretty much at one hundred percent.

Laurie, overprotective mother that she is, doesn’t want to discuss things like murder and near decapitations in front of Ricky. But Ricky fills the conversational space; he’s in a very talkative mood this morning.

“I hit the ball yesterday.”

“Yeah, I’m sorry I missed it. I heard it was a home run.”

“Mom tell you that?”

“She did. She’s very proud of you.”

“I just hit it a little bit, and then the other team made a lot of errors.” He turns to Laurie. “That’s not a home run, Mom.” He gives me a little eye roll, a gesture that seems to say that we guys should know better than to believe women when it comes to something like baseball.

“I thought it was great,” Laurie says.

Laurie and I basically take turns walking Ricky to and from school. He goes to School Number 20, which is about a fifteen-minute walk from our house. It’s where I went to school, and it looks absolutely the same.

When it’s my turn, as it is today, I often take Tara and Sebastian with us, which becomes their second walk of the morning. But Laurie says she’d like to come along today, and suggests we leave the dogs at home. It seems like a strange request, but I wait until we’ve dropped Ricky off to ask what’s going on.

“I know you want to talk some more about what happened last night. Coincidences bug you, and you want to look into it.”

“How did you know that?”

“You’re not exactly inscrutable, Andy.”

“I need to work on that.”

She holds up a set of car keys. “Let’s go,” she says, and we walk back to our car and head over to the murder scene.

If you ever want to attract a crowd, wrap yourself in police tape. Long after a criminal event has occurred, people seem drawn to the scene by the presence of that tape, as an apparent signal that “excitement occurred here.”

But when it comes to bringing out the masses, police tape takes a distant backseat to media trucks, which in turn pale next to reporters and cameramen.

Local news stations have a weird habit of sending those poor people out to the scene of events that have long been over. For example, the other day the Giants signed a free agent running back, and the local sportscaster reported the news at six o’clock in the morning from outside the empty stadium. The reason it was empty is that the season doesn’t start for five months, and the running back that was signed was in Milwaukee, where he lives.

But the media people are here at the murder scene, as are heaping helpings of police tape, so crowds are milling about. There are also some cops here, probably wrapping up their investigation, as well as making sure no one enters the house.

Having been a member of the Paterson Police Department, Laurie pretty much knows everyone on it. I know a lot of them also, but since my connection to them has mostly been as a defense attorney attacking them in cross-examination, they have always disliked me rather intensely. I thought my defending Pete, one of their own, might make them think more kindly of me. It hasn’t.

So Laurie walks over to talk to a detective named Danny Alvarez, who greets her with a big smile. They talk for a while, and while I can’t hear what they’re saying, I see Laurie point back toward me. Alvarez looks my way, and loses the smile.

After maybe three minutes, Alvarez walks off the porch and down the driveway, and Laurie comes over to me. I ask her what’s going on.

“Alvarez is setting it up for us.”

Before I get a chance to ask what that means, Alvarez comes back up the alley and gives Laurie the thumbs-up sign. “Let’s go,” she says, and I follow her down the same driveway Alvarez had gone down. “We’re going to talk to Downey’s landlady,” she says. “Her name is Helen Streiter.”

When we get to the back of the house, I point to the screen door to Downey’s house. “Pete said that door was open, that we might have scared the killer off.”

We look around at the surroundings. There are houses and driveways everywhere, from both Downey’s street and the one behind it. There is not, as I suspected, a doghouse.

“You want to talk to me?” a voice says, and we see that there’s a woman waiting at the screen door in the back of the house next door to Downey’s. She’s wearing something that’s either a housecoat or a dress, but whatever it is, she looks like she bought it the year the Cubs won the World Series.

She stands by the open door, with no obvious inclination to let us inside. I can see that she is barefoot, which in context does not seem particularly surprising. “The cop said I was supposed to talk to you, but I ain’t got all day,” she says with a sneer, immediately getting on my nerves.

“You rushing to get ready for the prom?” I ask.

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

Laurie frowns slightly at the unproductiveness of my comment. “Ms. Streiter, we just want to ask you about Gerry Downey’s dog,” Laurie says.

“Dog? He ain’t got no dog. I don’t allow no dogs.”

“Are you sure about that?”

“Course I’m sure. Anyway, Gerry hated dogs. There’s a dog across the street that b

arks during the night, when he hears noises out on the street. Gerry told me once he was going to shoot the damn thing.”

“And it’s not possible he could have had a dog without you knowing about it?” I ask.

“A dog that don’t bark? That he doesn’t have to let out? That nobody knows about? Come on … gimme a break.”

Gerry Downey didn’t own a dog, and didn’t like them. Even if those things weren’t true, he wouldn’t have been allowed to have one where he lived. But he broke into our foundation building and stole one, just before he was brutally murdered.

“He must have stolen Cheyenne for someone else,” I say, as we’re driving home.

“But not the person that killed him” is Laurie’s reply. “Because that person wouldn’t have left her there.”

“So we need to find out who Downey had been in contact with in the last days before his death,” I say.

“We only need to if we really care why Downey stole the dog. You have her back, and Downey is dead. Some people might consider that resolution enough.”

I nod. “True. On the other hand, whoever authorized the theft of Cheyenne is still out there, and might do it again. Which would violate our protection philosophy.” Willie and I feel that once we rescue a dog it is in our protection, and we have full responsibility for it for the rest of its life, even after we find it a home.

“Why am I not surprised?” Laurie asks.

I respond with a question of my own. “You think we should put Super Sam on it?”

Laurie considers this for a moment. On some recent cases, I have used Sam Willis, my accountant-turned-computer-hacker-extraordinaire, to track movements and contacts of certain subjects of our investigations. He often does this by hacking into phone company records, learning whom the person spoke to. He also can access GPS records and determine where the person’s cell phone has been, since each one has a GPS built into it. It’s not one hundred percent, but people and their cell phones are rarely in different locations.

Dachshund Through the Snow

Dachshund Through the Snow Bark of Night

Bark of Night Muzzled

Muzzled Hounded

Hounded The Twelve Dogs of Christmas

The Twelve Dogs of Christmas Dog Eat Dog

Dog Eat Dog Black and Blue

Black and Blue Leader of the Pack

Leader of the Pack Open and Shut

Open and Shut Leader of the Pack (Andy Carpenter)

Leader of the Pack (Andy Carpenter) Sudden Death

Sudden Death Deck the Hounds: An Andy Carpenter Mystery

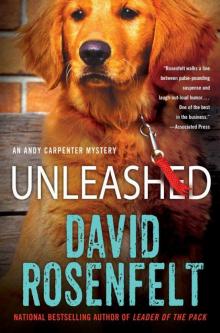

Deck the Hounds: An Andy Carpenter Mystery Unleashed

Unleashed First degree ac-2

First degree ac-2 Open and Shut ac-1

Open and Shut ac-1 New Tricks ac-7

New Tricks ac-7 One Dog Night

One Dog Night Heart of a Killer

Heart of a Killer Who Let the Dog Out?

Who Let the Dog Out? Bury the Lead

Bury the Lead Fade to Black

Fade to Black Dog Tags

Dog Tags Dead Center ac-5

Dead Center ac-5 Collared

Collared Airtight

Airtight Rescued

Rescued Play Dead

Play Dead Sudden Death ac-4

Sudden Death ac-4 Blackout

Blackout Deck the Hounds--An Andy Carpenter Mystery

Deck the Hounds--An Andy Carpenter Mystery On Borrowed Time

On Borrowed Time Play Dead ac-6

Play Dead ac-6 Dog Tags ac-8

Dog Tags ac-8 First Degree

First Degree New Tricks

New Tricks Outfoxed

Outfoxed