- Home

- David Rosenfelt

Dead Center ac-5

Dead Center ac-5 Read online

Dead Center

( Andy Carpenter - 5 )

David Rosenfelt

David Rosenfelt. Dead Center

(Andy Carpenter – 5)

Copyright

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

To Debbie

Acknowledgments

This is the page on which I usually thank the people who helped me with the book, but this time I’m not going to do it. Why should I? Do you think that if the positions were reversed they would thank me? Trust me… no way.

In fact, on any of my previous books, have they ever thanked me for thanking them? Have they ever said, “Hey, thanks for thanking me. I’m really thankful for that?” No.

That’s the thanks I get.

They spend their time thinking, not thanking. They’re thinking… “How come I wasn’t thanked first? How come so-and-so was thanked before me?” They don’t come out and say it, but that’s what they’re thinking… I’m just thankful I can see through it.

Thanking people is a thankless job.

I’ve just figured out a way to get back at them. I’ll thank them in alphabetical order-and in that way I’ll teach them a lesson on the evils of elitist thank-ism. Here goes: Stacy Alesi, Stephanie Allen, John and Carol Antonaccio, Nancy Argent, Susan Brace, Bob Castillo, David Divine, Betsy Frank, George Kentris, Emily Kim, Debbie Myers, Martha Otis, June Peralta, Les Pockell, Jamie Raab, Susan Richman, Robin Rue, Nancy and Al Sarnoff, Norman Trell, Kristen Weber, Sandy Weinberg, and Susan Wenger.

Maybe this page will accomplish something: Perhaps they’ll see the error of their ways. But do I want them to apologize? Thanks, but no thanks.

On a more serious note, I would like to sincerely thank those readers who e-mailed me with feedback on the previous books. Please continue to do so at [email protected].

Thank you.

• • • • •

DO YOU GET SPIRITUAL credit for celibacy if it’s involuntary?

This is the type of profound question I’ve asked myself a number of times during the last four and a half months. This is the first time I’ve asked it out loud, which may say something about my timing, since the person hearing it is my first date in all that time.

Actually, “date” may be overstating it. The quite beautiful woman that I am with is Rita Gordon, who when she’s not dressed in a black silk dress with an exceptional cleavage staring straight at me, spends her days as the chief court clerk in Paterson, New Jersey. Rita and I have become fairly good friends over the last few years. No small accomplishment, since her daily job is basically to ward off demanding and obnoxious lawyers like me.

We’re in one of North Jersey’s classier restaurants, which was her choice entirely. I have absolutely no understanding why certain restaurants succeed and others don’t. This one is ridiculously expensive, the menu is totally in French and impossible to understand, the portions are so small that parakeets would be asking for seconds, and the service is mediocre. With all that, we had to wait two weeks to get a reservation on a Thursday night.

The extent of my relationship with Rita until now has basically been to engage in sexual banter, an area in which her talents far exceed mine. She has always presented herself as an expert in dating, sex, and everything else that might take place between a man and a woman, and has volunteered to go with me on this “practice date” as a way to impart some of that knowledge to me.

I can use it, as evidenced by my celibacy question.

“There’s an example of something you might want to avoid asking a date,” says Rita. “Celibacy can be a bit of a sexual turnoff.”

I nod. “Makes sense.”

“On the other hand, swearing off sex increases your dating possibilities, since you could also go out with guys.”

I shake my head. “Finding dates is not my problem; there are plenty of women that seem to be available. The problem is my lack of interest. It’s the ironic opposite of high school.”

Rita looks me straight in the eye, though that doesn’t represent a change. She’s been looking me straight in the eye since we sat down. She takes eye contact to a new level; it’s like she’s got X-ray vision and is looking through to my brain. I’ve never been an eye-contacter myself, and I almost want to create a diversion so she’ll look away. Something small, like a fire in the kitchen or another patron fainting headfirst into his asparagus bisque.

“How long has Laurie been gone?” she asks.

I must be healing emotionally, since it’s only recently that a question like that doesn’t hit me like a knife in the chest. Laurie Collins was my private investigator and love of my life. She left to return to her hometown of Findlay, Wisconsin, where she will probably fulfill her dream and become chief of police. I had always wanted her dream to be a lifetime spent with me, Andy Carpenter.

“Four and a half months.”

She nods wisely. “That explains why women are coming after you. They figure you’ve had enough time to get back into circulation, to get your transition woman behind you.”

“Transition woman?”

She nods. “The first woman a guy has a relationship with after a serious relationship ends. It never works out; the guy’s not ready. So women wait until they figure the guy’s had his transition and he’s ready to get serious again. The timing is tricky, because if she waits too long, the guy could be gone.”

I give this some thought, but the concept doesn’t seem to fit my situation, so I shake my head. “Laurie was the first woman I went out with after my marriage broke up. And she transitioned me; I didn’t transition her.”

“Have you spoken to her since she left?”

Another head shake from me. “She sent me a letter, but I didn’t open it.” This is not a subject I want to be discussing, so I try to change it. “So give me some advice.”

“Okay,” she says, leaning forward so that her chin hovers over her creme brûlée. “Call Laurie.”

“I meant dating advice.”

She nods. “Okay. Don’t do it until you’re ready. And when you do, just relax and be yourself.”

I shift around in my chair; the subject and the eye contact are combining to make me very uncomfortable. “That’s what I did with Laurie. I was relaxed and myself… right up until the day she dumped my relaxed self.”

For some reason, on the rare occasions when I talk about my breakup with Laurie, I emphasize the “dumping” without getting into the reasons. The truth is that Laurie had an opportunity to fulfill a lifetime ambition and at the same time go back to the hometown to which she has always felt connected. She swore that she loved me and pretty much begged me to go with her, but I wanted to be here, and she wanted to be there.

“You’ve got to move on, Andy. It’s time…” Then the realization hits her, and she puts down her wineglass. “My God, you haven’t had sex in four and a half months?”

It’s painful for me to listen to this, partially because it’s true, but mostly because the waitress has just come over and heard it as well.

I turn to the waitress. “She meant days… I haven’t had sex in four and a half days. Which for me is a really long time.”

The waitress just shrugs her disinterest. “I’m afraid I can’t help you with that. More coffee?”

She pours our coffee for us and departs. “Sorry about that, Andy,” Rita says. “But four and a half months?”

I nod. “And I have no interest. The other day I found myself in the supermarket looking at the cover of Good Housekeeping instead of Cosmo.”

“Pardon the expression,” she asks, �

��but you want me to straighten you out?”

The question stuns me. She seems to be suggesting that we have sex, but I’m not sure, since I can count the number of times women have propositioned me in this manner on no fingers. “You mean… you and me?”

She looks at her watch and shrugs. “Why not? It’s still early.”

“I appreciate the offer, Rita, but I’m just not ready. I guess I need sex to be more meaningful. Sex without love is just not what I’m looking for anymore; those days are behind me.” These are the words that form in my mind but don’t actually come out through my mouth.

What my mouth winds up saying is, “Absolutely.” And then, “Check, please.”

• • • • •

RITA LEAVES MY house at three in the morning. She had agreed to come here instead of her place because I would never leave Tara, my golden retriever and best friend, alone for an entire night. But she had shaken her head disapprovingly and said, “Andy, for future reference, you might want to avoid telling the woman that you prefer the dog.”

I don’t walk Rita to the door, because I don’t have the strength to. Even after summoning all the energy I have left, all I’m able to do is gasp my thanks. She smiles and leaves, apparently pleased at a job well done.

“Well done” doesn’t come close to describing it. There are certain times in one’s life where one can tell that one is in the presence of greatness. Sex with Rita would be akin to sharing a stage with Olivier or having a catch with Willie Mays or singing a duet with Pavarotti. It is all I can do to avoid saying, “Good-bye, maestro,” when she leaves.

As soon as she’s gone, Tara jumps up on the bed, assuming the spot she so graciously gave up during Rita’s stay. She stares at me disdainfully, as if disgusted by my craven weakness.

“Don’t look at me like that,” I say, but she pays no attention. We both know what the payoff to buy her respect will be, but the biscuits are in the kitchen, and it’s going to take an act of Congress to get me out of bed. So instead I just lie there awhile, and she just stares for a while, both of us aware how this will end. I won’t be able to fall asleep knowing she did not get her nighttime biscuit, and right now sleep is my dominant need.

I get up. “Why must it always be about you?” I ask, but Tara seems to shrug off the question. I stagger into the kitchen, grab a biscuit, and bring it back into the bedroom. I toss it onto the bed, not wanting to give her the satisfaction of putting it in her mouth for her.

Determined to remain undefeated in our psychological battles, Tara lets the biscuit lie there, not even acknowledging its presence. It will be gone in the morning when I wake up, but she won’t give me the satisfaction of chowing down while I’m awake.

Tara and I have some issues.

When I wake up in the morning, I use a long shower to relax and reflect on my triumph with Rita last night. “Triumph” may be too strong a word; it was more a case of me accepting a sexual favor. But it seems to have the effect of improving my outlook. I know this was a one-night stand, but in some way it helps me to see a life after Laurie.

I take Tara for our usual walk through Eastside Park. The park is about ten walking minutes from my home on Forty-second Street in Paterson, New Jersey. The look of the park has not changed in the almost forty years I have lived here. It’s a green oasis in what has become a run-down city, and I appreciate it as much as Manhattanites appreciate Central Park.

The park is on two levels, with the lower level consisting basically of three baseball fields, two of which are used for Little League. The two levels are connected by a winding, sloping road that we used to refer to as Dead Man’s Curve, though I’m quite sure it did nothing to earn the name. Looking at it from an adult perspective, it’s not even scary enough to be called Barely Injured Man’s Curve.

The upper area is where Tara likes to hang out, because there are four tennis courts, which means there are lots of discarded tennis balls. I don’t even bring our own anymore; Tara likes to find new ones for herself.

We throw one of the tennis balls for a few minutes, then stop off on the way home for a snack. I have a cinnamon raisin bagel and black coffee. Tara opts for two plain bagels and a dish of water.

I love spending time with Tara; we can just sit together with neither of us feeling the need to talk. I’ve had a lot of good friends trying to “be there” for me since Laurie left, but Tara has been the best of all, mainly because she’s the only one that hasn’t tried to fix me up.

I’ve become something of a celebrity lawyer in the last few years because of a succession of high-profile cases that I’ve won. The excitement and intensity of those cases, coupled with a twenty-two-million-dollar inheritance I got from my father, have left me spoiled about work and incredibly choosy about the cases I accept.

In fact, in the four and a half months of life without Laurie, I’ve only had two cases. In one I represented a friend’s brother, Chris Gammons, on a DUI, which we won by challenging the accuracy of the arresting officer’s testimony. I took the case only after getting Chris to agree to enter an alcohol rehab program, win or lose.

Chris was also my client in the other case, which was a divorce action brought by his wife. She was apparently not impressed by my cross-examination of the arresting officer and was a tad tired of living with a “loser drunk,” which is the quaint way she described Chris in her testimony.

I’ve filled in the rather enormous gaps in my workday by becoming one of the more prominent legal talking heads on cable television. I’ve somehow managed to get on the lists that cable news producers refer to when they need someone to comment on the legal issues of the day. Generally, the topic is a current trial, either a celebrity crime or a notorious murder. I go on as a defense attorney, and my views are usually counterbalanced in the same segments by a “former prosecutor.” There seems to be an endless supply of former prosecutors.

I’m to be on CNN this morning at eleven-fourteen. They’re incredibly precise when informing me of the starting times, but then I can sit around for hours waiting for the interview to actually begin. I’ve finally gotten wise to this, and I show up as late as possible. Today I’m planning to arrive at eleven-twelve for my eleven-fourteen segment.

That gives me plenty of time to stop off at the Tara Foundation, a dog rescue operation that Willie Miller and I run. We finance it ourselves, the costs evenly provided for by my huge inheritance and the ten million dollars Willie received in a successful civil suit. Willie spent seven years on death row for a murder he didn’t commit, and after I got him a new trial and a subsequent acquittal, we sued the real bad guys for the money.

Willie and his wife, Sondra, do most of the work at the foundation, though lately I’ve been able to help a lot more than I could when I was working more regularly. Together we’ve rescued more than seven hundred dogs in less than a year and placed them in good homes.

Willie has taken two dog training classes in the past month, which in his mind qualifies him to change the act to Siegfried, Roy, and Willie. As far as I can tell, the only command he gets the dogs to obey is the “eat biscuit” command, but in Willie’s mind he’s turning his “students” into canine geniuses.

When I arrive at the foundation, Willie is working with Rudy, the dog he describes as the most difficult case in his entire training career. Rudy is a German shepherd, generally considered one of the smarter breeds, and he’s living up to that reputation by being smart enough to ignore Willie.

Willie has decided that the only possible reason for his lack of success in training Rudy is that Rudy has only learned to speak German. Unfortunately, Willie, who butchers English on a regular basis, hasn’t had occasion to learn much German, so he’s somehow latched onto schnell.

“Schnell,” Willie says as Rudy just sits and stares at him. “Schnell… schnell,” Willie presses, but Rudy doesn’t move. Willie is about six two, a hundred and eighty pounds, and he seems to athletically glide as he moves. As he gives commands to the oblivious Rudy, he

steps around him as if he’s a fashion photographer doing a photo shoot, trying to find just the right angles.

“He doesn’t seem to want to schnell,” I say, and Willie looks up, surprised that I am there.

“He schnelled a few minutes ago,” Willie says. “He probably saw you come in and didn’t want to do it with you here.”

I’m aware that Willie speaks only the one German word, has no idea what it means, but uses it all the time. “What exactly does he do when he schnells?” I ask.

“It depends on how I say it.” He turns back to Rudy and says, “Schnell. Schnell, boy.” His tone is more conciliatory, but Rudy doesn’t seem any more impressed. In fact, he just seems bored and finally lies down and closes his eyes.

“Good boy… good boy,” Willie says, rushing over to pet Rudy, though failing to wake him in the process.

“So ‘schnell’ means sleep? Very impressive,” I say. “There’s not another trainer in the state that could have gotten that dog to schnell.”

I only stay for about ten minutes, discussing with Willie which of the local shelters we will go to this weekend to rescue more dogs. We’ve placed eleven this week, so we have openings. Every dog we rescue would otherwise be killed in the county shelters, so we are always anxious to fill whatever openings we have.

I arrive at the CNN studios in Midtown Manhattan at ten-forty-five, which gives me some time to hang out in the city and decide how I’d like to get ripped off. I could play three-card monte with the shady guys huddled against buildings, leaning over their makeshift tables, or I could spend four times retail for something in the thirty-five electronics stores on each block, or I could take a tourist bus ride stuck in Manhattan traffic. Instead I choose to pay forty-eight dollars to park my car, a price that would be reasonable if I were parking it in a suite at the Waldorf.

I get into the studio five minutes before my segment is to begin. The host, a genial man named Spencer Williams, is just finishing a segment on the expected automobile traffic during the Labor Day weekend. According to the experts, there is going to be a lot of traffic, a major piece of breaking news if ever I’ve heard one.

Dachshund Through the Snow

Dachshund Through the Snow Bark of Night

Bark of Night Muzzled

Muzzled Hounded

Hounded The Twelve Dogs of Christmas

The Twelve Dogs of Christmas Dog Eat Dog

Dog Eat Dog Black and Blue

Black and Blue Leader of the Pack

Leader of the Pack Open and Shut

Open and Shut Leader of the Pack (Andy Carpenter)

Leader of the Pack (Andy Carpenter) Sudden Death

Sudden Death Deck the Hounds: An Andy Carpenter Mystery

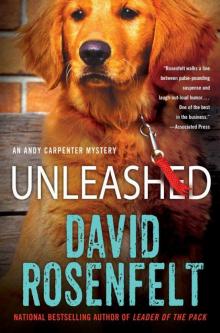

Deck the Hounds: An Andy Carpenter Mystery Unleashed

Unleashed First degree ac-2

First degree ac-2 Open and Shut ac-1

Open and Shut ac-1 New Tricks ac-7

New Tricks ac-7 One Dog Night

One Dog Night Heart of a Killer

Heart of a Killer Who Let the Dog Out?

Who Let the Dog Out? Bury the Lead

Bury the Lead Fade to Black

Fade to Black Dog Tags

Dog Tags Dead Center ac-5

Dead Center ac-5 Collared

Collared Airtight

Airtight Rescued

Rescued Play Dead

Play Dead Sudden Death ac-4

Sudden Death ac-4 Blackout

Blackout Deck the Hounds--An Andy Carpenter Mystery

Deck the Hounds--An Andy Carpenter Mystery On Borrowed Time

On Borrowed Time Play Dead ac-6

Play Dead ac-6 Dog Tags ac-8

Dog Tags ac-8 First Degree

First Degree New Tricks

New Tricks Outfoxed

Outfoxed